The pavilion features the waters of Brazil – its rivers and mangroves, the birthplace of the fertility of life, a natural inheritance that underlies all discourse about sustainability on the planet. With its tensile steel structure and lightweight white fabric, the pavilion is a fabric onto which videos are projected, creating an immersive atmosphere of variable images, sounds, aromas, and temperatures, over an area of undulating, shallow water through which the pavilion’s visitors may walk. It is a place of interaction, of an arresting scenic character. It is a stage for the visualization of nature and culture focused both on preservation and on a future made sustainable through technology.

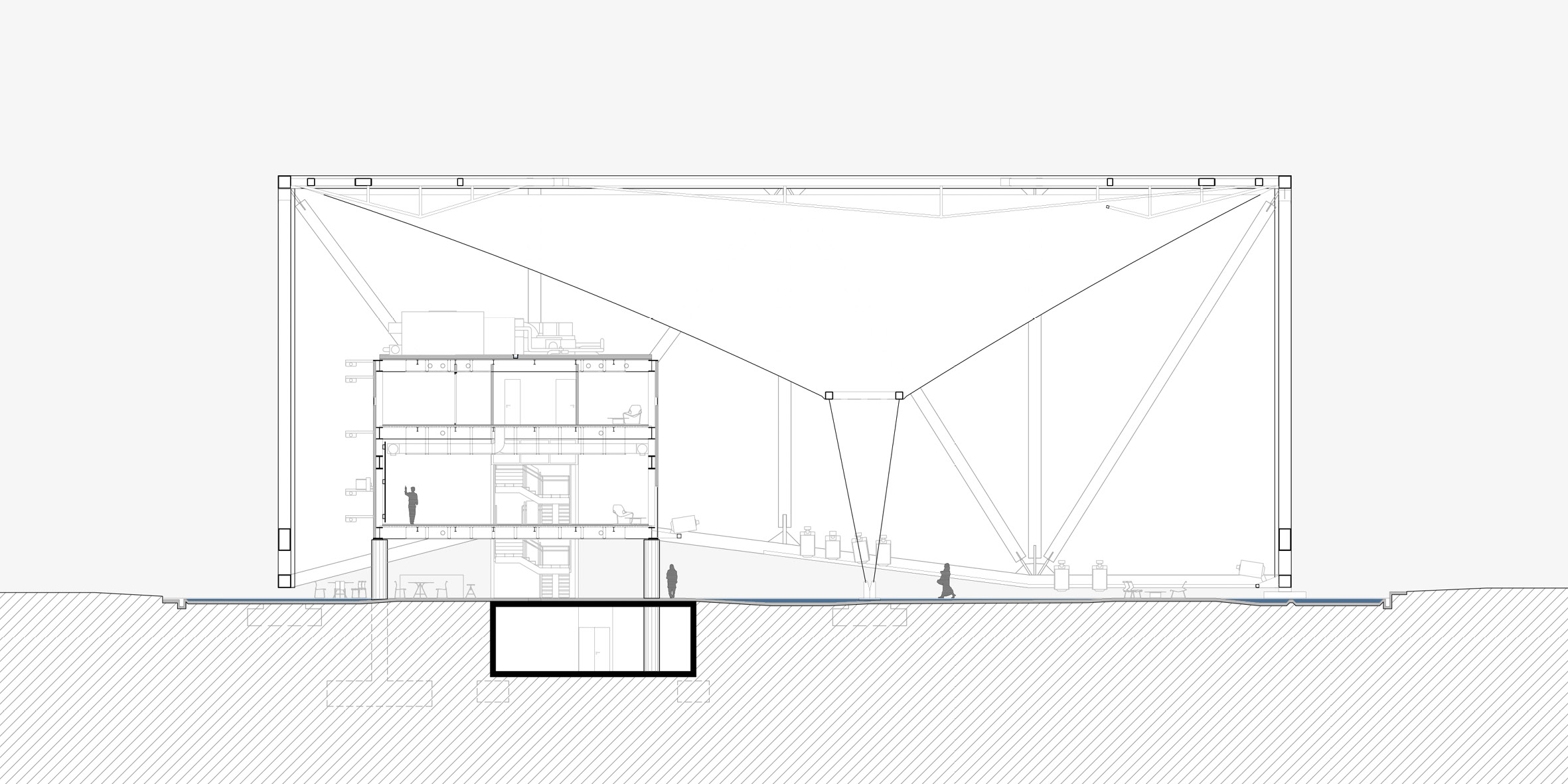

As in times of flood, when a river overflows its banks, inundating what was once land, the project floods, with a thin layer of water, the whole land of Brazil in Dubai. A uniform, dark topography, made of black-pigmented, sanded, non-slip concrete, derives its poetic motif from the Rio Negro in the Amazon basin. On this canvas are depicted meanders, beaches, and backwaters, creating a grand plaza of water. It is shielded by a tensile structure 48 meters wide and 18.5 meters tall; four vertical panels making up a covering, an impluvium, secured by cables anchored to the water mirror. During the day, this structure shades and protects the waters; at dusk, it makes the pavilion a luminous, floating cube. Immersed in projections, sounds, vapors, and subtle aromas, this space forms the essence of the proposed museum experience, whose theme is the fluvial waters of Brazil.

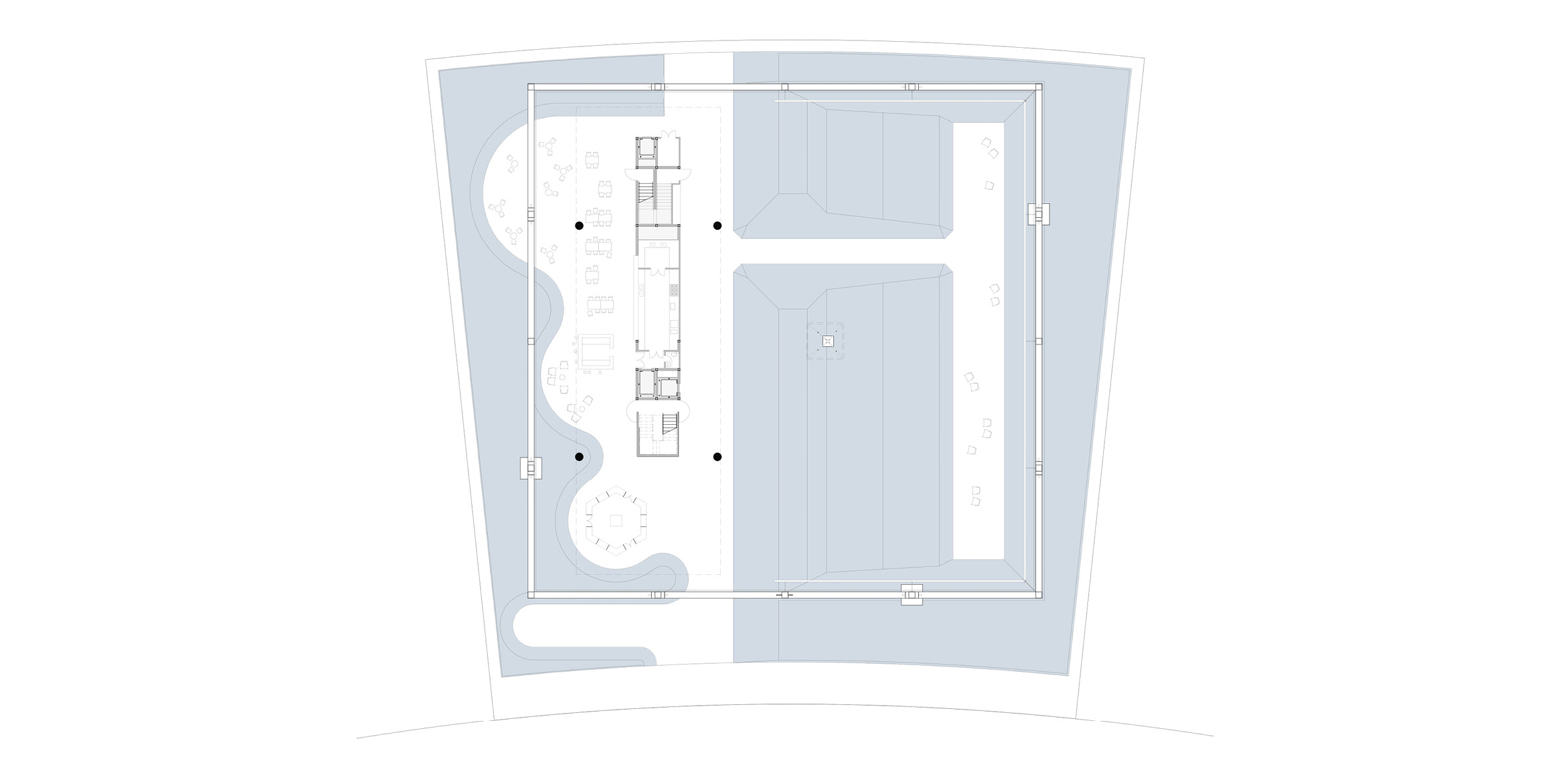

Visitors wishing to enter the water without wetting their feet will be offered Goldon boots, made famous in Venice, worn their overshoes at times of acqua alta. Access to the pavilion and walks around it can be made in its dry areas, where facilities complementary to the exposition are also located, such as a café, restaurant, and shop. These are contained in a separate, suspended, trellised volume that projects over the water plaza, in the manner of the houses on stilts, or palafitas, found in northern Brazil. On the air-conditioned first floor, accessed by stairs and a large capacity elevator, is a multi-purpose room for lectures, debates, movies, and small-scale shows. The lighting is completely controlled; a high-resolution screen is envisaged for presentations in ambient light. From the foyer, visitors have a privileged view of the water plaza below. This space may be used for complementary exhibitions, such as delicate or valuable objects. This floor and the next also have spaces for private meetings with Brazilian government officials and for technical use. On the roof, out of sight, are the firewater reservoir, air conditioning machines, and museum devices, such as image and light projectors, speakers, and sprinklers for aromas.

The structure makes it clear that the ground floor is the primary area for visitors, and that access becomes more restricted the further we move away from it. Added to this is its structural clarity, making it quick to assemble and disassemble; indeed, it does not require the kind of large-scale transportation that the exhibition might suggest. As is often the case with Brazilian architecture, its structural logic arises as an inseparable part of its architectural logic and the logic of its use, in this case, museography. The pavilion makes use of materials from around the world but with the same concept that has always characterized our architectural style: contemporary hollow. Allied to the small amount of construction involved, this coherence entails considerable gains from the point of view of economy and sustainability.

Finally, water is the central element of the proposal, with its associations with our long and profound relationship with our rivers, it becomes, here, a construction material: the support for the exhibition. Eschewing images that diminish the complex diversity of our natural resources or conceal an urgent critical consciousness about the future of the planet, we present the pavilion as a grand water plaza over which hangs a great solar cloud, embracing its visitors and encouraging them to participate actively in a Brazilian environmental experience.

The structure was envisioned in steel, both in the roof of the pavilion and in the space beneath. The pavilion presents a tensile structure with large trusses on its four facades, from whose upper edges are stretched the fabric of the roof, tensioned so as to take the form of a concave impluvium of four faces that converge in a circular water spout positioned slightly off-center.

The fabric is reinforced with steel cables that form the ridges of the impluvium and which, passing through a traction ring are taken down and tied at a single point to the ground, inside the water mirror. The resulting geometry, as in any tensile structure consisting of elastic elements, is not entirely flat, with the ridges curving upwards from their center (along with the steel cables) with a curve of the order of 5 percent along their length, while the fabric tensioned between the cables curves almost imperceptibly downwards.

In the horizontal plane along the top of the trusses of the facade is envisioned a compression ring, formed by the beams of the facade and by two more beams inserted in the former, rotated and crossed over each other so as to form struts between the nodes of the facade trusses. This whole set of steel bars is detached from the cover, creating pleasing shadows thrown onto the translucent fabric.

The fabric is a Precontrant fabric by Serge Ferrari, which features a flexible structure of high tenacity PET micro-cables coated with several layers of polymers and finished with a dirt-resistant surface treatment, offering low solar factor translucence and avoiding excessive heat gains. The internal volume has trusses in both of its longitudinal facades, each supported by two pillars, resolving in a rational manner the large proposed cantilevers.

The Brazilian Pavilion chooses water as its central theme of focus and reflection. The landscapes and ecosystems of the rivers and the mangroves, the forests and the byways of the savannah (the cerrado and the sertão). Inland Brazil, with its stilts and riverside communities, its indigenous peoples, and the “crab men” of the urban peripheries. A country “at the margin of history”, as Euclides da Cunha put it a century ago, but whose geography and culture, rich, diverse, and powerful, constitute a great asset for the sustainable development not only of Brazil but also of the whole planet. “The Amazon is the place of places” in the world today, writes the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. “It is there that a gigantic cultural stew is being cooked,” and in the rest of Brazil and the world “we have no idea what’s going on,” he says.

Formed by the decomposition of the leaves of the forest, the dark and crystalline water of the Rio Negro is the poetic motif of the meandering landscape created in the pavilion: a water plaza, or lake. So too is the mangrove, repository of immense fertility, the cradle of great biodiversity in the encounter between the river, the land, and the sea. “Landscape of amphibians, of mud and mud”, according to the poet João Cabral de Melo Neto. An image of a fertile country in fraternal contact with the neighboring nations of South America. A country is less known than the one that is familiar from its coastal regions, which since the time of its colonization has looked outwards towards Europe.

“It is ideas that travel, not materials,” says the Paraguayan architect Solano Benítez. We do not seek literally to recreate Brazilian landscapes in Dubai, with real fish or trees. Rather, we hope to reinterpret a Brazilian way of thinking about the relationship between construction and landscape, creating synesthetic and immersive atmospheres, combining the stimuli of sounds, aromas, temperature, and humidity, projected images on the lateral fabric walls and the internal, faceted faces of the roof, and the water surfaces on the floor.

The ambiance of the pavilion is created by somewhat abstract projections of vegetation, river springs, waterfalls, the meetings of rivers, feathered art, and indigenous body paintings, with powerful chromatic intensity. These are accompanied by variations in the humidity of the air, the vaporization of water in the environment, subtle and changing aromas of flowers, fruits, and mangroves, and sounds that alternate between indigenous songs, such as the Bororo fertility rituals, and the “mangue beat” of urban rock from Chico Science.

To this general ambience is added another level of information: short projections, with specific themes and narratives, at specific times, and occurring in different regions of the water plaza. They are projection-events, during which visitors are invited to enter the water, becoming active participants in the narrated stories. They are learning experiences informed by the content, such as, for example, audiovisual projections displaying the microorganisms of the mangrove, Amazonian water lilies, the flooded landscapes of the Pantanal of Mato Grosso and of Marajó Island, byways, streams and swamps, the technological potential of cocao and annatto (the condiment and food-dye from the seeds of the achiote tree), engineering works such as canals, dams and locks, river transposition systems and irrigation of dry areas, and projects to encourage river navigation. As well as projections of a scientific nature there are others, of an artistic and critical nature, such as Claudia Andujar’s photographs taken among the Yanomami peoples, the series “Dog without feathers” by Maureen Bisiliat, Cildo Meireles’s “rio oir” sound work, research into flying rivers by Artur Lescher, or the ephemeral landscape of rubber buoys created by Hector Zamora on São Vicente beach in “Recanto das Crianças”, at the 27th São Paulo Biennial.

The water plaza is not only a space for visual contemplation but also a place of enjoyment and interaction, of partying. It is the stage for the most important activities of the pavilion, such as acoustic musical performances, dance, and theater presentations that will exploit its daring characteristics. It takes its inspiration from the urban installation “Auditorium for delicate issues” by Guto Lacaz, which will be recreated on the water mirror.

Water is the primordial source of all life on earth. It is also an important means of transportation and communication for human civilization, and a source of enjoyment and sociability, adding a rich fruitfulness to inhabited environments. At the same time, it is a natural resource that is increasingly under threat, from scarcity and contamination. As the country with the greatest wealth of water in the world, Brazil must pursue an international policy for the defense and enjoyment of the water, a policy based on the preservation and enhancement of natural wealth through technology. This is the focus of the Brazilian Pavilion at Expo’2020.

Winner of the Building of the Year 2023 Prize from Archdaily website

Published by the websites Archdaily and Dezeen and the magazines Projetoand AV – Arquitectura Viva

Nominated to MCHAP – Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize